Buyers keep hearing that DTC balls come from “the same factory” as the tour giants—but they still worry about hidden trade-offs, fragile supply chains, and whether the technology is truly shared at all.

Chinese OEMs and big brands do share manufacturing platforms and mid-tier technology, but they do not share complete flagship recipes or IP. For B2B buyers, the safe assumption is “similar window, not same ball”—and your job is to verify it with molds, QC data and supply-chain checks.

The article treats “shared tech” as a testable claim, not a slogan. We’ll first define what can and cannot be shared, then move into a practical OEM audit checklist, supply-chain risk map and the real cost of quality control.

Marketing often suggests any Chinese factory can stamp your logo on a Pro V1 clone, but the shared platform is narrower than that—and over-selling “same factory” can backfire badly with informed golfers.

Tech is shared at the level of materials, machines and mid-tier constructions, not at the level of complete tour-flagship recipes. Big brands lock their best IP inside vertically integrated plants, while Chinese and Asian OEMs sell access to similar construction windows; your job is to prove performance with QC data and launch-monitor tests, not with slogans.

From a rules standpoint, there are only conforming and non-conforming balls. Weight, size, symmetry, initial velocity and overall distance limits apply whether the ball is made in Massachusetts, Korea or Guangdong. Clearing that gate means “legal to play”, not “identical to a specific flagship”.

On top of that gate, Chinese OEMs usually run three main families: 2-piece Surlyn balls for range and promo, 3-piece ionomer balls for value performance, and 3-piece urethane balls, most commonly with injection-molded TPU covers. Tour flagships often use cast thermoset urethane with more complex curing and tooling, giving a higher spin and feel ceiling at higher cost.

Independent lab work shows this OEM world is a spectrum. Some DTC and house-brand balls out of third-party plants match or beat big-brand consistency, while other budget models from similar regions are clearly “avoid” products. Country and factory labels tell you where balls are made, not how tightly they are controlled.

In practice, what’s shared vs proprietary looks like this:

| Dimension | Usually shared across brands/OEMs | Typically proprietary to flagships | Risk if misunderstood | Buyer next step |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core & compression | Material families, broad compression bands | Exact recipe, gradient and cure curve | Over-promising “same feel” | Ask for compression ranges, not clones. |

| Mantle layers | Ionomer families, basic thickness windows | Specific blends and multi-layer gradients | Different spin vs your reference ball | Compare sample data to a named tour ball. |

| Cover material | Surlyn/ionomer, TPU urethane platforms | Cast urethane blends and surface chemistry | Calling TPU a 1:1 Pro V1 equivalent | Market honestly as TPU or Surlyn urethane. |

| Dimple tooling | Generic OEM-owned patterns | Brand-specific molds and layouts | IP conflict, clone accusations | Secure dedicated molds for your product. |

| QC windows | Basic checks on weight and size | Tight statistical windows and deep analytics | Quality drift over seasons | Lock QC ranges and test plans into contracts. |

✔ True — You can share platforms, not someone else’s flagship

Independent Asian OEMs often run multi-layer ionomer and TPU urethane constructions for several brands, including mid-tier lines of big names. You are buying access to that platform, not their tour ball formula.

✘ False — “Same factory” equals “same Pro V1 recipe”

Flagship cores, covers and dimples are locked behind contracts and proprietary tools. Expecting a 1:1 copy is unrealistic and dangerous from an IP and brand-trust standpoint.

How do IP rules and materials platforms shape “shared tech” reality?

OEM contracts usually draw a hard line between factory IP (generic molds, standard recipes) and customer IP (paid-for tooling, special constructions, artwork). For flagship projects, big brands add NDAs, non-competes and volume or territory exclusivities.

Material names are only umbrellas. “Urethane” covers include many TPU and cast systems; “ionomer” hides numerous blends and hardness levels. Several brands may ride the same resin supplier and machine park, while differentiating through layer design, cure profiles and dimple geometry.

A good way to think about it: your Chinese OEM can put you on a similar materials and process ladder as big brands, but your exact rung—feel, spin, durability—is something you co-design and pay to protect. If a factory offers a “tour ball with your logo” on generic molds, treat it as a red flag, not an opportunity.

What audit checklist should you use to vet a golf ball OEM?

It’s easy for an OEM to claim they “follow USGA rules” and “have made tour balls”, but those lines don’t tell you if they can protect your molds, hold tolerances or scale without nasty surprises.

A practical OEM audit starts with three control points: who owns the molds, who defines QC windows and who funds any USGA/R&A submissions. You then validate the story with a 12-ball QC report, launch-monitor data versus a reference ball and clear customs and chemical compliance evidence.

For non-engineer buyers, group the audit into four pillars:

-

IP & molds – Ownership, exclusivity and exit terms.

-

Quality & testing – Equipment list, sample QC reports, launch-monitor access.

-

Operations & lead time – Sample and mass-production weeks, realistic MOQs, peak-season plan.

-

Compliance & landed cost – HS 9506.32 knowledge, REACH/Prop 65 testing, DDP capability.

In China, many serious factories quote samples in days and mass runs in weeks, with lower MOQs for 2-piece Surlyn and higher for 3-piece urethane. The best ones can also package REACH/Prop 65 testing and DDP into a single workflow so you see your real landed cost up front.

Here’s a compact OEM audit checklist:

| Dimension | Question to ask | Good answer looks like | Bad answer looks like | Next action for you |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molds & IP | Who owns my molds and patterns? | Named tooling list, clear ownership, exit plan | “Factory molds; we reuse as needed” | Insist on tooling list and ownership. |

| QC capability | What test equipment do you have? | Compression, hardness, X-ray/CT, launch monitor | “We just hit balls on the range” | Request recent QC report before samples. |

| Conformance | USGA/R&A experience? | Knows process, has past listings or reports | “Maybe a client did it once” | Treat “tour-level” claims as marketing. |

| Lead times | How do timings change in peak season? | Clear calendar, realistic buffers | “Same all year, don’t worry” | Ask for seasonal OTIF history. |

| Compliance | Can you handle HS, REACH, Prop 65, DDP? | Specific markets, labs and Incoterms explained | “We ship FOB only, you handle the rest” | Budget external help or switch supplier. |

| RFQ behaviour | How fast and detailed is a quote? | 12–24h, structured by construction and volume | Multi-day silence or one-line prices | Use RFQ as a filter for maturity. |

✔ True — USGA/R&A listings are often project-driven

Many Chinese OEMs only submit when a client funds the cost. A lapsed listing can sit beside a very capable process that still hits the same technical window.

✘ False — “Not on the list this year” means “low-end factory”

Judge the plant by its data, equipment and discipline, not solely by whether someone renewed paperwork for a given SKU this season.

Do you own your molds, or does the OEM control them for multiple brands?

Mold ownership is often the single clearest line between a generic OEM ball and a defensible product line. If the factory owns and freely reuses the dimple tools, your “model” can quietly show up under other logos.

You’ll typically see three models: buyer-owned dedicated molds, OEM-owned generic molds, and shared molds with partial exclusivity. For serious brands, dedicated molds with written inventory lists and transfer clauses are the norm. Your contract should define where molds are stored, who insures them and how quickly they must be shipped or scrapped if the relationship ends, so your trajectory and visual identity remain portable.

What risks arise when big brands acquire your OEM?

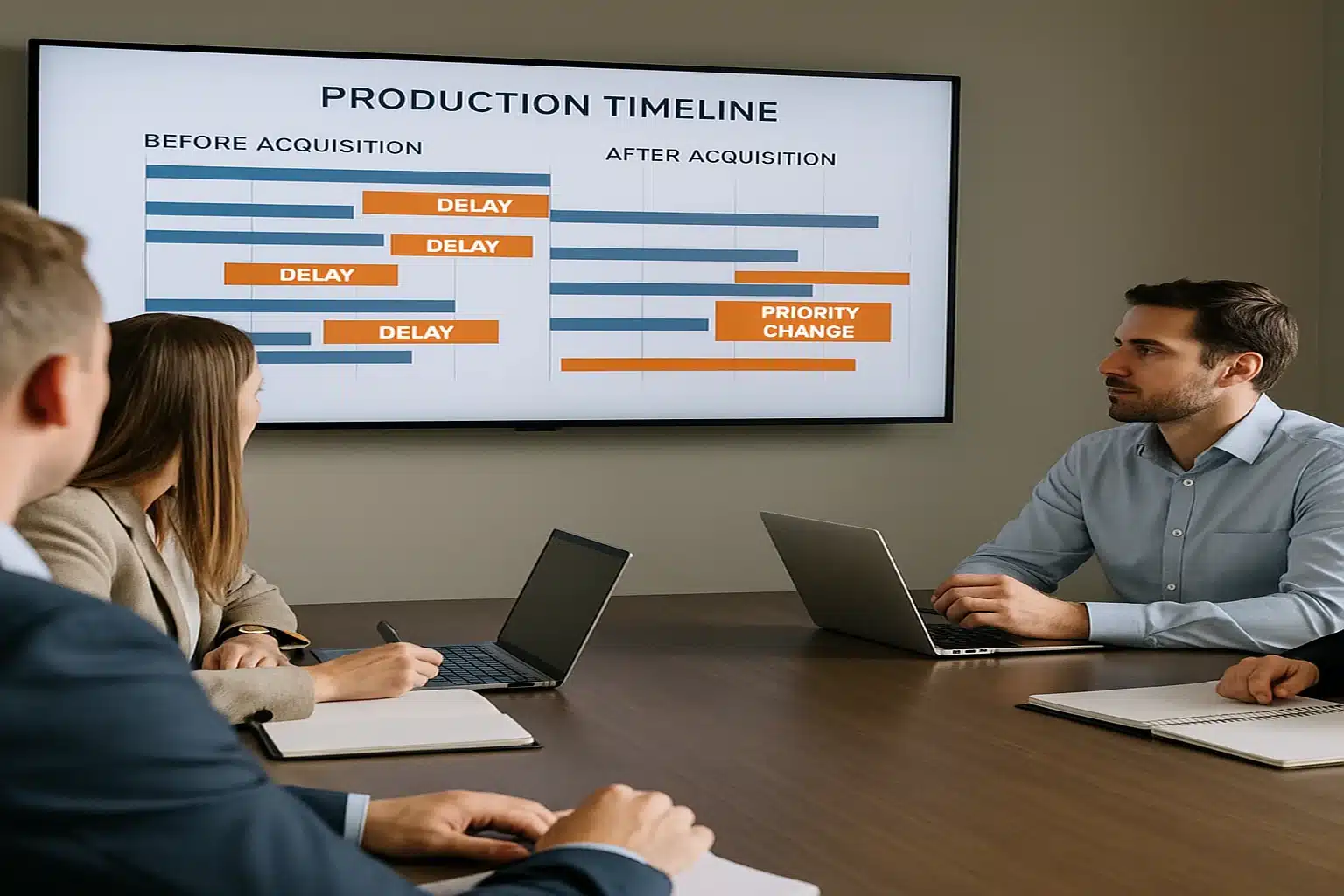

If your hero product depends on a factory that just became a strategic plant for a tour brand, your place in the production schedule can change overnight—even if your own volumes stay the same.

When a big brand acquires an OEM, that plant’s first duty becomes the parent’s own balls, and smaller DTC or house brands tend to slide down the pecking order. In a concentrated ball industry, mid-size brands should assume this risk and pair any main OEM with at least one independent Chinese or regional backup.

After an acquisition, the internal pecking order usually becomes:

-

Parent company’s flagship and mid-tier lines

-

A small set of strategic external accounts

-

Remaining DTC, private-label and corporate clients

At the same time, physical shocks—a fire in a high-volume plant, a regional outage, sudden local regulation—can ripple through multiple brands that rely on the same facility. That’s the dark side of a very efficient, highly concentrated supply base.

China’s OEM landscape is more distributed. Several medium-sized factories across major industrial belts can handle Surlyn and urethane constructions with competitive lead times. For a mid-size brand, an independent Chinese OEM where you are a top-10 account may actually be more stable than a captive plant where you are line item number ninety-something.

A simple “before/after” checklist helps you watch for trouble:

| Signal | Before stress or acquisition | After stress or acquisition | What it means for you | Suggested response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead times | Drift by days, explained | Jump by weeks, vague reasons | You’re losing slot priority | Negotiate SLAs, add a second OEM. |

| MOQs | Stable, workable tiers | Sudden doubling or rigid minimums | Cash and inventory pressure | Split SKUs across plants. |

| Communication | Quick, specific replies | Slow, generic replies, staff turnover | Lower strategic importance | Escalate; treat as early warning. |

| Engineering input | Willing to tweak specs | Push to “standard models only” | Less differentiation | Secure your own tooling; explore options. |

| Pricing & terms | Predictable, incremental changes | New surcharges or strategic pricing | You’re funding the transition | Re-benchmark vs independent Chinese OEMs. |

How do DTC brands fall victim to the OEM pecking order?

Many DTC brands mistake a shared factory for a strategic alliance, but for the plant they are often just flexible filler volume. When capacity tightens, big contracts, then strategic regional partners, get protected first.

Typical failure modes: lead times quietly stretch from eight to twelve weeks; colorful SKUs or special numbers are “temporarily” paused; MOQs jump just high enough to strain your cash flow. Because these changes arrive one by one, founders often adapt instead of stepping back and reading the pattern.

Track three simple KPIs: on-time in-full delivery rate, average RFQ response time, and how often “capacity issues” are cited in a year. If all three trend the wrong way, start sizing a backup plan instead of assuming things will simply “go back to normal”.

What is the true cost of quality control in OEM golf balls?

On paper, that ultra-low quote looks perfect for a value-tier ball. But when compression windows blow wide open, concentricity drifts and coatings chip early, your “savings” can reappear as returns, discounts and bruised brand reviews.

The real cost of QC is the cost of catching and scrapping bad balls before customers ever see them, not the price of a single lab machine. Factories that invest in compression, hardness and X-ray checks and launch-monitor validation must charge more per dozen, while ultra-cheap offers usually push performance and compliance risk back onto you.

A practical buyer-level view of QC focuses on a few measurable dimensions:

-

Weight and diameter distribution

-

Compression window and spread for cores and finished balls

-

Cover hardness and durability

-

Core centering and concentricity

-

Launch-monitor dispersion vs a trusted reference ball

Your acceptance protocol can be simple. Ask for a 12-ball QC sheet with averages and ranges for weight, size and compression, plus evidence on concentricity and surface quality. Add a short launch-monitor comparison against a benchmark ball at defined swing speeds. You don’t need perfect numbers; you need tight clustering and stability across batches.

When comparing OEM offers, think in terms of lifecycle cost, not unit price:

| Offer type | What the quote looks like | What’s usually happening behind the scenes | Risk for your brand | How to respond |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Cheap” quote | Very low FOB, vague on QC and compliance | Minimal sampling, wide windows, low scrap | Inconsistent feel, surprise failures | Add strict QC clauses or walk away. |

| “Controlled” quote | Slightly higher price, detailed QC and DDP | Real equipment, staffed lab, planned scrap | More predictable performance and delivery | Treat as baseline; negotiate scope, not %. |

✔ True — Logistics and compliance sit inside quality, not beside it

Correct HS classification, REACH/Prop 65 testing and labeling are part of delivering a “good ball” to your warehouse. A perfect product stuck at customs is still a failure.

✘ False — DDP is just a convenience upgrade

DDP-capable OEMs are usually the ones who understand the full cost stack and have repeatable processes. That mindset tends to show up in lab work as well.

Why does a 12-hour quote often signal a mature manufacturing system?

Slow, fuzzy quoting usually reflects internal chaos: no clear BOMs, no standard costing and weak coordination between sales and production. Fast, structured quotes tend to come from factories that already know their material windows, capacity limits and compliance paths.

Treat RFQ behavior as a low-cost stress test. A serious OEM answers within 12–24 hours with options by construction (2-piece Surlyn vs 3-piece urethane), volume tiers, lead times in and out of peak season, and compliance options (with or without testing, FOB vs DDP). That level of clarity is hard to fake—and is a strong predictor of how they will perform once you sign a PO.

FAQ

Can a Chinese OEM legally make a Pro V1-equivalent ball for my private label?

No OEM can legally sell you a 1:1 Pro V1 clone with your logo; flagship balls are protected by patents, contracts and tooling control. What a serious Chinese factory can offer is a distinct design in a similar performance window, not a copied construction.

Even when an OEM has built balls for tour brands, it remains bound by NDAs and non-compete clauses. Duplicating a flagship recipe would jeopardise its biggest customers and reputation. The smart approach is to brief your supplier on target speeds, spin and feel, then co-design a unique 3-piece urethane or high-end Surlyn ball. In your marketing, talk about “tour-style performance tested against leading balls”, not “the same as X”.

If an OEM has no current USGA/R&A listing, can the balls still be tour-quality?

Yes. Lack of a current USGA/R&A listing often reflects economics and focus, not an inability to meet the standard; many Chinese factories only submit when a specific project funds the fees. You should judge quality through lab data and testing, not the paperwork alone.

Conformance testing and annual renewals cost money, and OEM margins can be thin. Plants may certify once to prove capability, then keep running the same tools and recipes without paying for yearly updates until a buyer needs a live listing. That means a non-listed factory can still build balls whose weight, size, symmetry and distance sit comfortably inside the allowed window. As a buyer, you should ask for historical test data, fresh QC reports and comparative launch-monitor results to confirm that real-world behaviour matches your performance tier.

How small can my first order be without ending up at the bottom of the factory’s priority list?

For 2-piece Surlyn balls, many Chinese OEMs can support pilot orders around a few thousand balls; 3-piece urethane usually starts higher. The key is pairing a modest first run with a clear ramp-up plan so the factory sees you as a future core account, not a one-off.

Minimums depend on cycle time and scrap risk. Simple Surlyn constructions are quick and forgiving, so factories can afford lower MOQs; urethane lines tie up more tooling and QC resources. When you negotiate, don’t focus only on the first PO size. Agree on a second-order option and indicative annual volume if KPIs are met, and talk explicitly about priority in peak season. That way, your early orders are framed as the first chapter of a growth story, not “spare-capacity filler”.

Are Korean, Vietnamese or Indonesian plants safer than Chinese OEMs for long-term brand building?

No country automatically guarantees better balls; Korea and Southeast Asia lean toward higher-cost, higher-complexity lines, while China offers broader capacity, lower MOQs and faster cycles. The right mix depends on your positioning, budgets and risk appetite, not the flag alone.

Korean and some Southeast Asian plants have long experience with complex urethane balls and can be great partners for premium lines, but often at higher MOQs and longer lead times once captive contracts are layered on top. Chinese clusters, by contrast, cover everything from range balls to serious DTC and mid-tier urethane, with strong advantages in speed and flexibility. Many brands therefore combine both: China for agile SKUs and cost control, plus at least one non-Chinese plant for diversification and specific halo products. The key is to audit individual plants, then decide which combination best matches your portfolio.

How can I verify that the launch-monitor data my OEM sends is trustworthy?

Treat OEM launch-monitor reports as a starting point: insist on full test conditions, side-by-side data against a named reference ball, and periodic spot checks at an independent fitter or retailer. You care more about consistency of the pattern than any single number.

At minimum, each report should list the device, club model and loft, swing speed, number of shots and test temperature. It should compare your ball to a known model so you can see differences in ball speed, launch angle, spin and dispersion. If you don’t own a launch monitor, book a short session with a local fitter using production balls a few times a year. You don’t need a giant dataset; you just need to confirm that real-world results sit within the same “window” the OEM promised.

Conclusion

At this point, “same factory as the big brands” should sound less like a magic phrase and more like a prompt for hard questions about IP, QC and supply-chain hierarchy.

Chinese OEMs operate on the same industrial platform as many global brands, but that does not mean you are quietly buying someone else’s tour ball. You can share material families, process windows and, with the right plant, tour-level QC—but not another brand’s flagship recipe or strategic priority. The safest move is to treat ‘shared tech’ as a hypothesis and then audit it with data, tooling control and diversified capacity.

Three principles can guide your sourcing:

-

Rules and data over rumours. Conformance limits and Ball-Lab-style QC tell you more than any “made in X” story.

-

Vertical integration is real. Big brands are pulling their very best tech back into captive plants, leaving OEM space for excellent but distinct products.

-

Independent Chinese OEMs are an advantage if you behave like an auditor. With structured checklists, realistic MOQ planning and clear QC and compliance expectations, you can turn “shared tech” from a risky marketing line into a reliable part of your brand’s value proposition.

As a next step, shortlist one or two candidate OEMs, send a structured RFQ based on this checklist, commission a 12-ball lab and launch-monitor comparison against your current gamer, and get mold ownership and exit clauses into the very first draft contract. Do that, and the question “Is the tech truly shared?” becomes less about myth and more about the disciplined way you use the OEM ecosystem.

You might also like — Can Chinese Manufacturers Produce Tour-Grade Golf Balls?