Buyers often assume a low-priced ball must be wildly inconsistent. In reality, consistency is driven by manufacturing tolerance and QC, not the logo price tag.

Cheap golf balls are not automatically less consistent than premium balls. As long as a model passes USGA/R&A rules, every conforming ball shares the same speed and distance ceilings; the real difference is how tightly each factory controls core centering, layer thickness and compression from ball to ball.

To answer the question like a serious buyer, we first need to define what “consistency” means in golf ball manufacturing, then separate price, branding and true QC performance.

What does “consistency” really mean in golf balls?

When players complain that a ball is “inconsistent”, they might mean distance gaps, strange curves in the air, or wedges that sometimes grab and sometimes skid. Without a clear definition, it’s impossible to judge whether a cheap or expensive ball is really at fault.

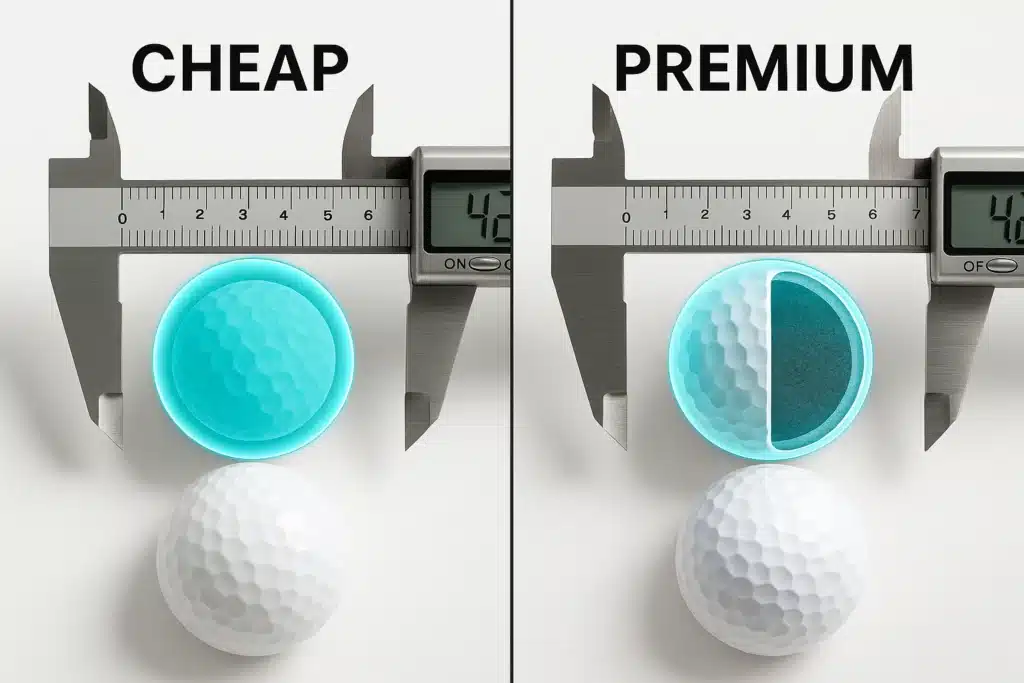

In golf ball manufacturing, “consistency” means that every ball in a batch matches its design window for weight, diameter, compression, hardness, concentricity and cover thickness. A consistent ball model produces tight dispersion in robot tests and small statistical variation from ball to ball, not just one impressive sample that happens to perform well.

At the rules level, USGA/R&A limits cover maximum weight, minimum diameter, spherical symmetry, capped initial velocity and the Overall Distance Standard (ODS). Once a model passes, every conforming ball – budget or tour-priced – shares the same outer guardrails. From there, the story is no longer “legal or illegal”, but “how tightly does production cluster around the design?”.

Within-model consistency is where factories truly differentiate. Ball Lab–style projects measure full dozens from retail, chart weight, diameter and compression, and flag any out-of-round, overweight, badly off-center or wildly off-compression balls as “bad”. The result is a bad-ball percentage and a picture of how tight or loose a model really is. For B2B buyers, a “good” factory is simply one whose production plots as narrow, boring bell curves instead of scattered dots.

Which factory-level tests define a consistent golf ball?

From a buyer’s perspective, consistency should be tied to measurable tests, not marketing claims. A professional factory will use a predictable toolkit to monitor every production batch.

The core tools are precision scales and ring gauges for weight and diameter, compression testers, Shore hardness meters, and – on serious lines – X-ray or CT to check core centering and layer concentricity. Optical systems validate dimple geometry, and rebound or velocity rigs ensure no ball comes off the face too fast. Samples from each lot – often 12–36 balls – are tested, and the factory tracks averages, standard deviations and reject rates.

When you ask about consistency, you should hear specific answers about instruments, sampling plans and reject criteria. If a supplier cannot describe its lab or show recent calibration certificates, it is not ready to support a brand that sells “tight dispersion” as a real value proposition.

Sticker price is the easiest thing to compare, so it often becomes a proxy for quality. That’s why many buyers assume a $20/dozen “budget” ball must have sloppier tolerances than a $50 tour model, even if both pass USGA tests and come from highly automated plants.

Cheap golf balls are not automatically less consistent than premium balls. Robot and Ball Lab–style testing shows that even Tier-1 tour balls can have measurable bad-ball rates, while some lesser-known OEM and direct-to-consumer models achieve extremely low defect percentages. Consistency depends on manufacturing discipline, not retail price.

Ball Lab reporting makes one point very clearly: even highly rated tour balls sometimes show several percent of balls classified as “bad”, while a few OEM or DTC models have achieved near-zero bad-ball samples. The difference lies in process control and QC culture, not in the logo or MSRP. A cheap ball from a disciplined factory can be far more consistent than an expensive ball from a factory that tolerates wider spreads.

Robot testing reinforces the risk: an out-of-balance ball can move more than 20 yards offline under identical swing conditions. That is a manufacturing problem, not a “cheap ball” problem. Once the USGA guardrails are met, the remaining question is simple: how many balls in each lot behave like the design, and how many behave like outliers?

✔ True — “Cheap” is about price, not physics

A low shelf price or OEM quote mainly reflects positioning, overhead and distribution. It tells you almost nothing about weight variation, compression spread or core centering until you see the QC data.

✘ False — “If it’s cheap, the factory must have turned off QC”

Reputable OEMs typically run value and premium balls on the same lines and through the same lab. The savings usually come from simpler constructions and lower marketing spend, not from skipping tests.

What does USGA conformity actually guarantee – and what doesn’t it?

For many buyers, seeing a model on the USGA or R&A conforming list feels like a quality badge. It is important to understand exactly what this does and doesn’t cover.

Conformity is a yes/no decision: the ball must meet limits for weight, diameter, symmetry, initial velocity and ODS distance. It does not grade feel, spin, dispersion or bad-ball percentage. A conforming ball can be average, good or outstanding in real-world consistency; the rules only ensure it isn’t designed to exploit non-spherical shapes or excessive distance.

There is also a cost angle. Each model on the list carries submission and maintenance fees, and frequent cosmetic or pattern changes can trigger new submissions. Many Chinese OEMs therefore certify a limited set of SKUs as capability proof, while using the same tooling and process windows for unlisted variants. An expired listing usually reflects a commercial decision, not a technical collapse.

How do construction and materials influence consistency and price?

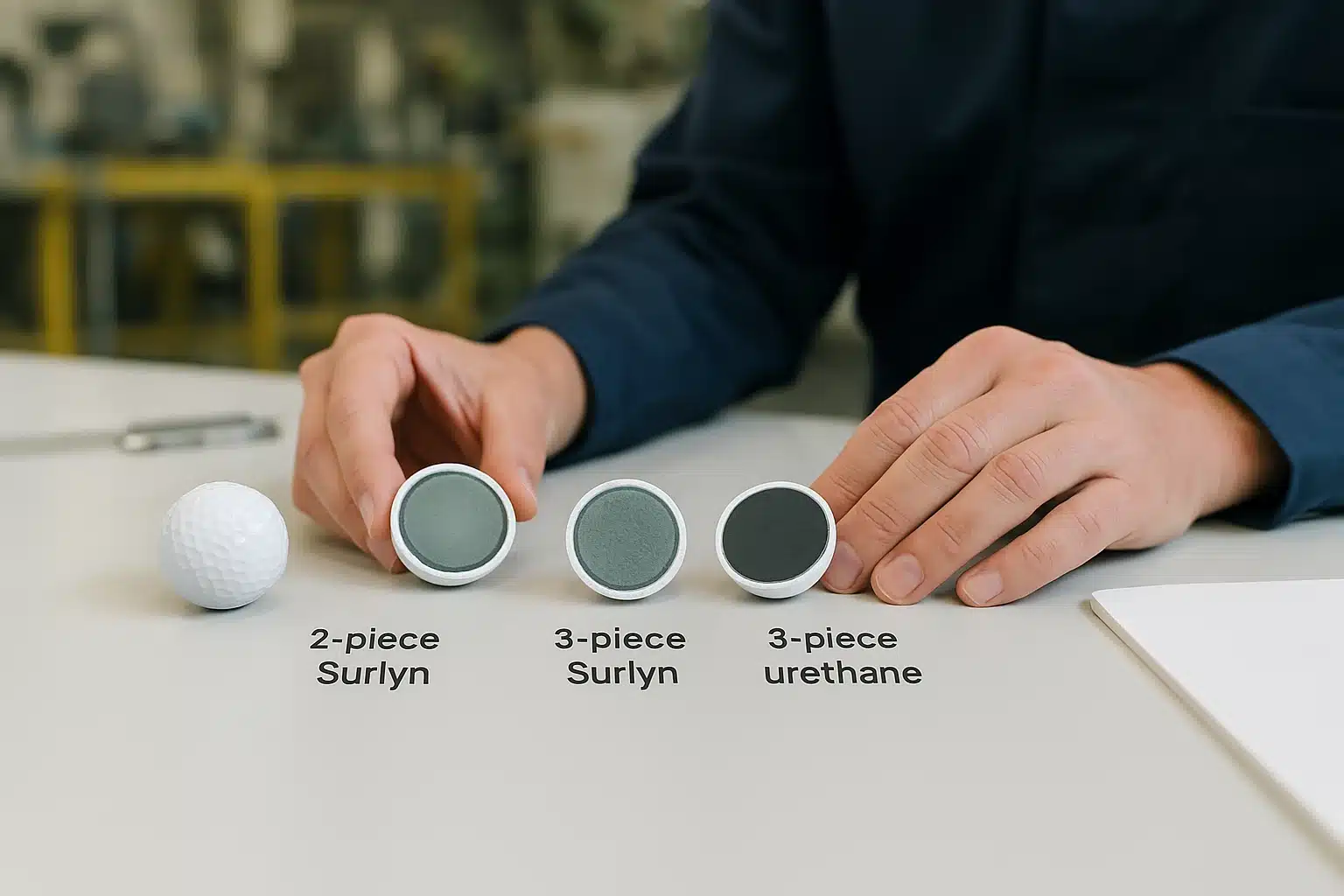

Premium balls usually mean multi-layer urethane covers and tour players on the box, while “cheap” often means 2-piece Surlyn. It’s tempting to assume that more layers and softer urethane automatically deliver better quality and consistency in every direction.

Construction and materials shape performance and cost, but they don’t automatically dictate consistency. A 2-piece Surlyn ball can be manufactured with very tight weight and compression tolerances, while a 3-piece urethane ball from a poorly controlled line can show larger variation between samples. Material choice mainly affects feel, spin and durability; consistency comes from process control.

A classic 2-piece Surlyn (ionomer) design is a large solid core with a tough, relatively firm cover: durable, low-spin off the driver and inexpensive to produce, ideal for high-loss golfers, ranges and promo projects. Three-piece designs add a mantle and, in urethane versions, a softer, thinner cover that separates long-game and short-game spin and softens feel. That extra layer, and the stricter cover tolerances, increase scrap risk and cost – which is why urethane balls sit at the top of the price ladder.

In major Chinese clusters, it is common for the same campus to produce 2-piece Surlyn, 3-piece Surlyn and 3-piece TPU-urethane balls. The construction changes; the underlying compression molding, injection and QC philosophy do not. You choose construction for your target golfer’s speed, loss rate and scoring needs; you choose factory and tolerance windows for how repeatable that performance feels from ball to ball.

✔ True — Material tier and consistency are different axes

Surlyn vs urethane mainly affects spin profile, feel and scuff resistance. A value Surlyn ball can still be extremely consistent if the process is well controlled.

✘ False — “Only multi-layer urethane balls can be built to tour-level tolerances”

Tooling, process capability and QC culture determine tolerances. When those are strong, a 2-piece ball can look just as clean under X-ray as a flagship urethane model.

To position your line-up efficiently, it helps to see constructions side by side:

| Decision dimension | 2-piece Surlyn value ball | 3-piece Surlyn mid-tier | 3-piece urethane “tour-style” | Recommended use case / takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driver distance | Long, low spin, very stable | Similar distance, slightly more spin tuning | Long, optimized for specific swing bands | Distance gaps are modest; use spin window to differentiate. |

| Wedge/short-game spin | Lower, more rollout | Medium | High, strong stopping power | Urethane where scoring and control really matter. |

| Durability (cover scuffs/cuts) | Very high | High | Lower, more sensitive | Surlyn for high-loss or heavy-use environments. |

| Cost per dozen | Lowest | Mid | Highest | Price gap reflects materials plus marketing, not just QC. |

| Perceived “premium” by golfers | Entry-level / range / promo | “Game improvement” feel | “Tour ball” image | Align construction with brand story and target margin. |

Where does the extra cost of “tour” balls really go?

Understanding the cost stack behind a $50/dozen tour ball versus a $20/dozen value ball helps separate true performance investment from pure marketing tax.

Manufacturing cost per ball covers rubber and resin, processing, paint, labor, energy and scrap – but by the time R&D, overhead, marketing, tour sponsorships and multi-layer distribution margins are added, it is only a slice of the final retail price. Public financial data for major golf groups show that sales and marketing spend alone can rival equipment manufacturing costs.

For OEM or DTC brands, the model is simpler: similar constructions run on the same lines but without global tour staffs and television campaigns. When you buy a well-specified OEM ball, most of your savings come from cutting logo and advertising spend, not from weakening the QC lab.

How can buyers independently verify a supplier’s consistency claims?

Suppliers will rarely admit that their defect rate is high or their lab is basic. For a buyer trying to launch or reposition a golf ball line, relying on brochures and pretty photos alone can lead to nasty surprises in the form of returns, complaints and lost accounts.

Serious buyers should treat golf ball consistency as a measurable KPI. Ask suppliers for recent QC reports on full batches, insist on seeing equipment lists and calibration records, and, where feasible, run independent tests – from simple saltwater float checks to lab compression and X-ray scans. A good factory will welcome this scrutiny and help interpret the data.

A practical workflow starts with factory data. Request full-batch QC reports on recent production lots: weight, diameter, compression and any visual or X-ray defects, ideally for 12–36 balls per lot. Ask for the lab equipment list and calibration schedule so you know how those numbers are generated. Clarify whether the factory has ever submitted balls to USGA/R&A and what they learned; you don’t need a certificate for every SKU, but you do want a partner that understands the rules.

On your side, simple saltwater float tests can reveal gross core off-centering, and basic compression checks via a third-party lab can confirm that you’re really getting the advertised spec. For hero SKUs, independent robot or launch-monitor testing gives you a concise picture of dispersion and spin. Established OEMs in Guangdong, Fujian and Zhejiang are used to this level of questioning and can usually accommodate small, data-driven projects when expectations are clear.

✔ True — USGA/R&A listing is a compliance gate

Being on the conforming list means the ball met weight, size, symmetry and distance rules at the time of test. It does not score consistency, feel or spin, and it can lapse purely for commercial reasons.

✘ False — “If a Chinese OEM doesn’t renew certification every year, their balls must have declined in quality”

Annual fees and frequent cosmetic changes make constant renewal expensive. Many factories prove capability once, then keep process windows tight while focusing certification budget where tour legality or marketing returns justify it.

To keep RFQs comparable, you can map supplier responses into a simple grid:

| Evaluation dimension | Strong supplier signal | Weak / risky signal | Buyer decision / next step |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lab equipment | Named instruments, calibration plan shared | “Basic checks only”, no specifics | Green light vs request upgrades / walk away |

| QC reporting | Recent batch data with distributions | Only old or sample-based reports | Accept, or insist on pilot with strict inspection |

| USGA/R&A experience | Clear history, documents available | Vague, no supporting evidence | Decide if compliance knowledge meets your needs |

| Communication & response | Fast, structured, proactive trade-offs | Slow, generic replies, dodges hard questions | Proxy for issue-handling after order |

| MOQ & flexibility | Explains how small runs fit main lines and QC | “Small orders” with no QC detail | Clarify pilot strategy or treat as high risk |

Which supplier behaviors signal real consistency culture?

Beyond lab data, the way a supplier communicates about quality is often the best predictor of how they will handle your project.

Look for fast, structured answers that address your spec point by point. A mature OEM will suggest constructions and compression bands for your target golfer, explain trade-offs between 2-piece and 3-piece builds, and be candid about what they can and cannot guarantee. Openness about external labs, how they handle nonconforming lots and which SKUs they monitor most closely are strong green lights.

By contrast, ultra-low prices with vague QC answers, discomfort when you mention bad-ball percentage, or visible confusion around basic USGA concepts are all reasons to slow down, ask for more detail or walk away.

FAQ

If I switch from a $50 tour ball to a $25 value ball, how much consistency do I really lose?

In most modern tests, conforming value balls are very close to tour models in driver distance and basic dispersion. The bigger trade-off is usually in wedge spin and feel, not raw consistency. If your target golfers lose several balls per round, stepping down in price can be a net performance win.

Because all conforming balls share the same speed and distance ceilings, typical driver gaps are small – often only a handful of yards. Where urethane tour balls pull ahead is in short-game spin and control, especially from 30–70 yards. For high-handicap or price-sensitive segments, a durable, low-loss Surlyn ball can reduce penalty strokes and cost while maintaining tee-shot stability that is “good enough” for their skill level.

Can 2-piece Surlyn balls be legal for tour-level events?

Yes. Cover material has nothing to do with legality. A 2-piece Surlyn ball can appear on the USGA/R&A conforming list and be used in elite events as long as it meets all size, weight, symmetry, velocity and distance requirements.

The rules regulate geometry and performance, not whether the cover is ionomer or urethane. Tour pros overwhelmingly choose multi-layer urethane balls for performance reasons, but that doesn’t mean Surlyn balls are illegal or inherently low-end. For your brand, separate two messages: “This ball is tournament-legal” (rules) and “This ball offers tour-level short-game control” (performance), and make sure your construction matches whichever promise you make.

✔ True — Surlyn balls can be conforming and competition-legal

A Surlyn or 2-piece construction can fully comply with USGA/R&A rules and appear on the conforming list. Legality depends on tests, not on whether the ball is marketed as “tour” or “distance”.

✘ False — “Only multi-layer urethane tour balls can be used in serious events”

This myth can push buyers into unnecessary costs. Use urethane where the scoring benefit justifies the spend, not because you believe Surlyn is forbidden by the rule book.

Does seeing a ball on the USGA conforming list guarantee top-tier consistency?

No. The conforming list is a pass/fail compliance document, not a quality ranking. A listed ball has cleared key rules barriers, but it may still be average, good or outstanding in terms of bad-ball percentage, spin stability and feel.

Listing confirms that a sample passed the USGA guardrails. It says nothing about how tight the production distributions are month to month. That’s why independent testing can find several percent bad balls in some listed models and almost none in others. When you build a brand, treat conformity as non-negotiable for certain SKUs, then add your own consistency metrics and acceptance criteria on top.

Why do some Chinese factories stop renewing USGA/R&A certifications if their balls are still high quality?

Because certification renewals cost money and time, and each cosmetic or model change may trigger a new submission. In a thin-margin OEM environment, factories certify strategically instead of listing every SKU every year.

A factory that runs many private-label and range balls under different names can’t profitably certify all of them. Often it will submit representative models to prove capability, then apply the same process and tooling to unlisted variants aimed at non-tournament markets. When you see an expired listing, ask whether the construction or process has changed. If not, the physics are likely the same even if the paperwork isn’t current.

What is a realistic bad-ball percentage target for a private-label project?

For serious private-label projects, you should expect a bad-ball percentage in the low single digits at worst, and ideally close to zero on premium constructions. In contracts, define that number instead of relying on vague ‘high quality’ language.

Ball Lab data across many models show that even big-name tour balls are not perfect, while the best OEM or DTC offerings can approach zero bad balls in tested samples. Translating that into purchasing language might mean: “maximum 2% off-spec balls by agreed test method per lot, with credits or replacements if exceeded”. That turns consistency from a feeling into a measurable KPI for both sides.

How small can my order be without sacrificing consistency?

You can run small orders with good consistency if they are produced on the same lines, with the same tooling and QC, as the factory’s mainstream volume. The risk rises when ultra-low MOQs are pushed into side lines, old molds or semi-manual setups.

Modern OEMs often offer MOQs in the 1,000–3,000 ball range, but the key is where those balls will be made. If your pilot order shares core, cover, molds and lab routines with established SKUs, consistency should track their main business closely. If the supplier suggests a special “small-order solution” but can’t explain the equipment or QC plan behind it, treat that as a red flag and adjust MOQ or expectations accordingly.

Conclusion

The real decision is not “cheap versus premium logo”, but what level of consistency, spin profile and feel your target golfer truly needs — and how to buy that spec from the right factory at a sustainable cost.

Cheap golf balls are not doomed to be inconsistent, and premium logos do not guarantee perfection. For brand owners and buyers, the winning strategy is to specify measurable consistency targets, choose factories that can prove their process control, and invest only as much in materials and marketing as your golfers actually value.

You might also like — Private Label Golf Balls Economics: Tour-Quality on a Budget