What Does Golf Ball Dimple Count Mean—and How to Choose?

Golf ball dimple count tunes aerodynamics by tripping a turbulent boundary layer to balance drag and lift. Most modern balls use ~300–400 dimples. Don’t chase bigger numbers—choose by flight window: more & shallower tends straighter/lower apex; fewer & deeper can add lift/apex. Verify via simple headwind/crosswind A/B.

What does golf ball dimple count actually mean?

Dimple count is one part of the aerodynamic system. Dimples trip a turbulent boundary layer to cut pressure drag and tune lift. Count interacts with depth, diameter, edge angle, and layout to set lift/drag balance, wind stability, apex, and landing consistency—never distance by itself.

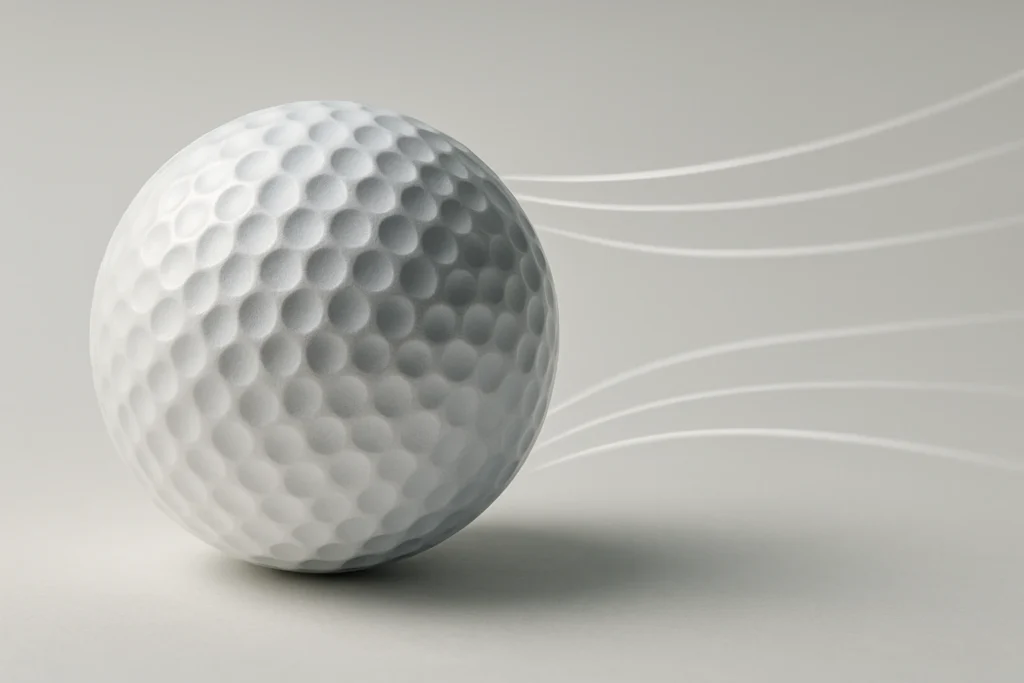

Put simply, dimples control airflow. A smooth sphere separates air early and sheds a large, messy wake. Add dimples and the boundary layer turns turbulent and more energetic, staying attached longer before separation. The wake shrinks, drag drops, and the ball can carry farther at a given speed and spin. But the number alone doesn’t define the window. Designers juggle count with depth, diameter, edge angle, and layout symmetry to hit a target lift/drag ratio that fits a player profile.

Two balls can share 332 dimples and fly differently if one uses deeper cups and sharper edges. Likewise, a 360-dimple build with shallower depth may fly straighter with a lower apex and better crosswind stability. Your takeaway: treat dimple count as a family tendency that guides testing, not a standalone performance ruler.

How dimples create a turbulent boundary layer

A dimple roughens the surface intentionally. That roughness energizes the thin air layer touching the ball, delaying separation and trimming the low-pressure wake. The result is less pressure drag, plus the possibility of useful lift when the ball’s spin and trajectory align. Designers vary depth, diameter, and edge curvature to steer how early the flow trips to turbulence, and how cleanly it leaves at the back.

Count vs. depth/diameter/edge: the coupling effect

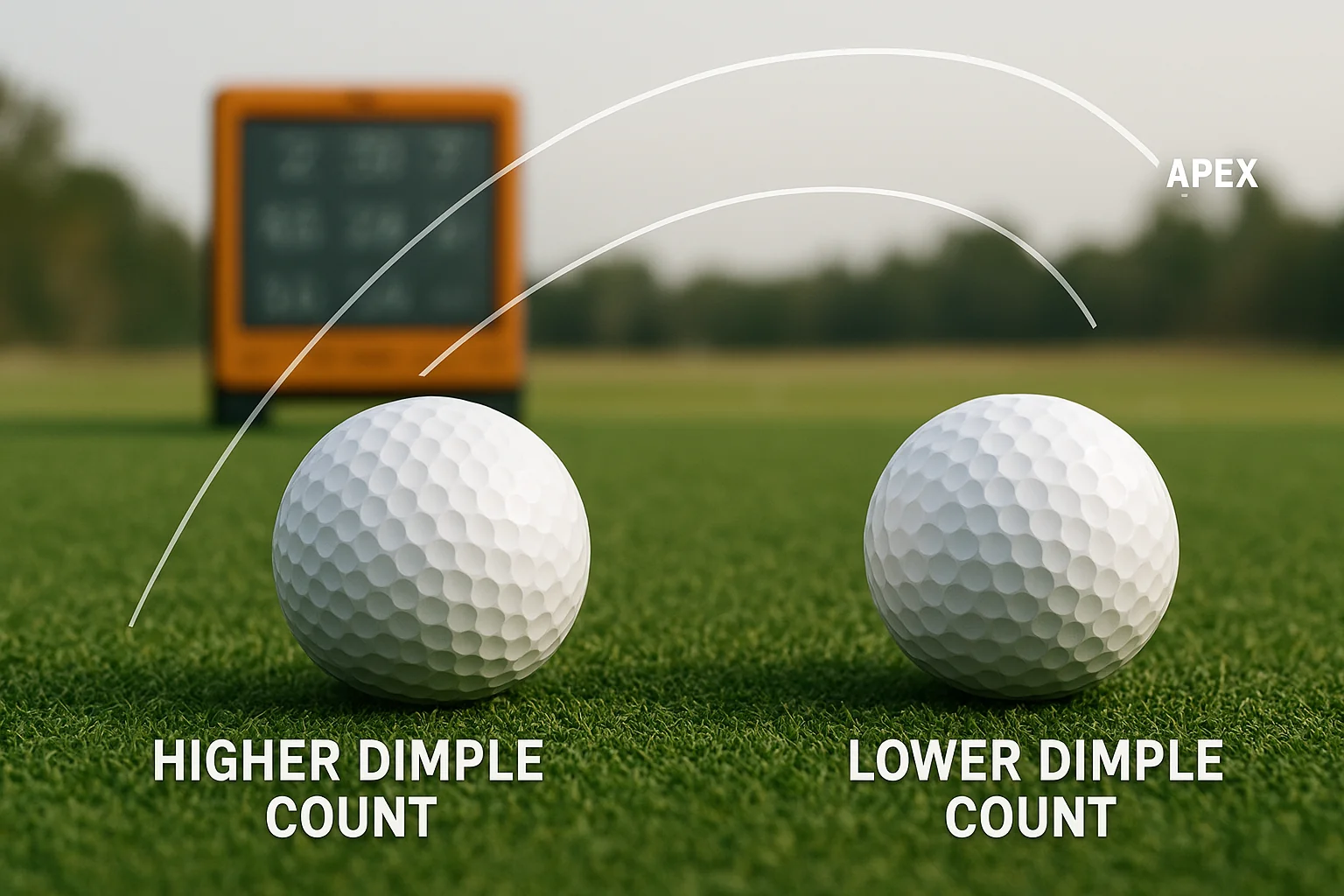

More dimples usually means smaller individual cups, often paired with shallower depths to avoid over-tripping and extra skin-friction drag. Fewer dimples typically means larger cups, where slightly deeper profiles can raise lift and apex. The edge angle (how sharp the dimple lip is) shifts separation behavior and can outweigh count. That is why 330–360 alone tells you very little without geometry.

Symmetry patterns (icosahedral, octahedral, seamless)

Layout governs uniformity. Icosahedral and octahedral patterns distribute dimples evenly across panels. Seamless designs erase traditional parting lines, aiming to reduce seam bias—the small directional effect that can show when shots are struck with a seam in a particular orientation. High-symmetry layouts support repeatable flight, especially in wind. If you study a dimple pattern icosahedral tiling versus an octahedral one, you’ll notice the different ways panel edges and vertices control edge density and, in turn, directional consistency.

Decision table — Aerodynamic variables that matter

| Aero variable | What it changes | Typical range | Design lever | When to push it |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimple count | Global tendency for drag vs. lift | ≈300–400 | # of cups | Stabilize or add apex by family tendency |

| Diameter | How early flow trips, wake size | ≈2.5–4.0 mm | Cup size | Match to speed and spin regime |

| Depth | Lift potential vs. drag | ≈0.10–0.25 mm | Cup depth | Add apex (deeper) or flatten (shallower) |

| Edge angle | Separation behavior | Mild–sharp | Lip geometry | Fine-tune wind stability |

| Layout symmetry | Directional consistency | Icosahedral / Octahedral / Seamless | Tiling | Reduce seam bias and dispersion |

✔ True — Dimple count is not a distance knob

Distance emerges from ball speed and spin window first, then aerodynamics refine stability and apex. Count must be read with depth, diameter, edge, and layout.

✘ False — “More dimples = farther”

Without geometry context, the count alone does not predict distance or wind stability.

Is a higher dimple count always better?

No. Higher counts often pair with shallower dimples that lower drag and can straighten flight, but they don’t guarantee distance or stability. Fewer-and-deeper can raise lift and apex for low-flight players. Outcomes depend on the full geometry—count, depth, diameter, edge, and layout.

Think in tendencies. Many designs with more-and-shallow feel flatter and more wind-stable for players who launch high or add spin. Conversely, fewer-and-deeper can help low-ball hitters climb to a healthier apex and carry. The edge angle can swing outcomes either way. If the lip is sharper, it may reclaim some lift lost with shallow depth or enhance stability with deeper cups. Small count deltas (e.g., 332 vs 338) are usually negligible without geometry context.

How many dimples do most golf balls have by type?

Most modern balls cluster around ~300–400 dimples: many 2–3-piece distance/all-around balls use ~320–360; tour-leaning 3-piece ~330–388; 4–5-piece ~320–352. Outliers below ~300 or above ~400 are niche and not inherently better.

These ranges are design conventions, not rules. The USGA/R&A do not set a hard limit on count; they regulate size, weight, speed, and symmetry. Manufacturers pick a count that supports their target window, then finalize the flight with depth, edge, and layout choices. If you’re researching the typical number of dimples on a golf ball, this is why sources cite similar bands yet still disagree on edge cases.

Typical ranges by construction (2pc/3pc PU/4–5pc PU)

Two-piece ionomer balls for distance and durability often sit ~320–360 with patterns aimed at straight, mid windows. Three-piece (ionomer or thin urethane) may use similar counts but lean on layers to tune spin. Tour-leaning 3-piece and 4–5-piece urethane frequently land ~330–352 with high symmetry to stabilize windows across speeds.

Special cases: wind/low-flight models (~300–340)

Designs marketed for wind or low flight often bias toward fewer or shallower tendencies within about ~300–340, depending on the rest of the geometry. The aim is lower drag and tighter dispersion, not just a smaller number.

Ultra-high counts (≳380) and low-count experiments (≲300)

Some brands explore ≳380 counts to achieve very uniform, low-drag feels or specific roll-out traits. Others test ≲300 with larger, deeper cups seeking a high apex. Both are niche strategies and should be judged by your own flight in real wind, not catalog copy.

Reference table — Typical dimple ranges by ball type

| Ball type / positioning | Typical dimple range | Flight tendency | Use case | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-piece (ionomer) distance | ≈320–360 | Mid to mid-high, straighter | Durability, range, value | Lower short-game spin |

| 3-piece (ionomer or thin PU) | ≈320–360 | Mid window, balanced | All-around control | Layers tune spin balance |

| 3-piece (tour-leaning PU) | ≈330–388 | Mid–high, precise | Scoring focus | Uses 348/352/388 patterns |

| 4–5-piece (tour PU) | ≈320–352 | Stable, segmented | Speed-adaptive control | Common 322/332/342 families |

| Wind/low-flight specialists | ≈300–340 | Lower apex, anti-float | Gusty venues | Depth/edge matter most |

| Ultra-high count | >≈380 | Very flat/straight | Specialty | Brand strategy |

| Low-count experiments | <≈300 | High apex potential | R&D, niche | Can be wind-sensitive |

How should you choose for your swing and wind conditions?

Choose by flight window and wind, not the number. If you balloon or drift, test families trending more-and-shallow (lower drag, straighter). If you fly too low, try fewer-and-deeper (more lift, higher apex). Confirm with same-club A/B in headwind and crosswind.

One-page selection table — symptoms to tests

| Issue | Likely tendency | What to test | Pass signal | Re-test when |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballooning headwind | Lower drag | Higher count + shallower depth | Apex −10–20% with carry held | 10–20 mph gusts |

| Crosswind drift | Stability & symmetry | High-symmetry/seamless layout | Offline −15–25% | New driver/shaft |

| Low apex / short carry | More lift | Fewer count + slightly deeper | Apex +10–15%, carry +4–8 yd | Cold dense air |

| Inconsistent landing | Better QC/layout | Proven molds, tight tolerances | Tighter roll variance | Each new lot |

Re-test after gear changes or seasonal air-density shifts.

Start from symptoms. What do you see in wind? Are peaks too tall with steep landings and lost rollout? Or do you fight low rockets that fall out too early? Then match the tendency and prove it on course-like wind, not just on a calm range.

Quick self-diagnosis: “too high/too low/side drift”

Make a short list: too high, too low, crosswind drift, or inconsistent landings. For too high or drift, test more-and-shallow patterns with high-symmetry layouts. For too low, try fewer-and-deeper tendencies. If landings vary, prioritize seamless or high-symmetry builds for repeatability.

A/B protocol: headwind + crosswind, 5–10 shots each

Use the same driver and swing. Hit 5–10 balls of Ball A into a headwind, then Ball B. Repeat for a crosswind. Record: apex height, offline distance at 250–270 yards, total, and roll. The better ball is the one with tighter dispersion and a flight you like, not just a single long outlier.

Interpreting “Flight/Spin” labels across a lineup

Brands publish “Low/Mid/High Flight” and “Low/Mid/High Spin” labels. Treat those as your first filter. Then let dimple tendency be your tuner. Within a family, the lower-flight models often lean toward shallower or higher-count tendencies; higher-flight models may leverage deeper or lower-count choices. Always verify with wind A/B.

What matters more than dimple count when selecting a ball?

Start with cover and compression, then layers and manufacturing consistency—use the dimple system last to refine the flight window. Cover sets feel and greenside spin; compression matches speed; layers balance spin; consistency controls dispersion.

This priority stack prevents you from over-weighting aerodynamics. If compression is misfit, you’ll fight launch and spin regardless of count. If cover is wrong for your goals, you’ll love the driver but hate wedge control, or vice versa. Once speed and spin are in a good corridor, dimples polish the shape.

Priority stack (1–5) and trade-offs

Cover first (urethane for control, ionomer for durability/straightness). Core compression next to match speed. Layers for spin balance across clubs. Consistency (concentricity/weight/seam) for dispersion. Then dimples for wind/apex tuning.

Compression vs driver speed (80–95 vs 95+ mph)

As a rule of thumb, ~80–95 mph players should stay near moderate compression to keep ball speed and launch efficient. ~95+ mph can use higher compression to manage driver spin without mushy feel. Both groups can benefit from the right dimple tendency, but only after compression is aligned.

Consistency: concentricity, weight tolerance, seam bias

Even the best geometry falters if the core is off-center or weight varies. Ask about tolerances, seam design, and paint thickness control. High-symmetry or seamless patterns reduce seam-direction variance, especially valuable in crosswinds.

Priority table — What you feel vs. typical trade-off

| Priority | Item | What you feel | Typical trade-off | When to choose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cover material & thickness | Soft/firm feel, greenside bite | PU scuffs sooner; ionomer is firmer | Control (PU) vs. durability (ionomer) |

| 2 | Core compression | Ball speed, driver spin | Over/under compress hurts speed | Match to driver speed |

| 3 | Layer architecture | Balance driver vs. wedge spin | Complexity/cost | 3–5 pieces for dual performance |

| 4 | Manufacturing consistency | Dispersion, distance spread | Tighter QC cost | Lower offline misses |

| 5 | Dimple system | Apex, wind stability | Must match 1–4 | Final flight tuning |

✔ True — Edge angle can outweigh count

Sharpening or softening the dimple lip shifts separation behavior across the entire pattern, often moving apex and stability more than a small change in count.

✘ False — Dimple count affects feel

Feel comes from cover, compression, and construction; dimples shape aerodynamics, not impact softness.

OEM/private label—how should you spec dimples and manage risk?

Anchor on proven 320–352 molds with high-symmetry layouts. Lock a full dimple system in the PO—mold ID, depth, diameter, edge angle, and layout—not just the count. Require size/weight/concentricity/paint reports and validate wind apex/side deviation on pilot lots.

For private label, clarity beats creativity at the start. Reference mold IDs and drawings. Count is necessary but not sufficient. The sampling plan must mimic real wind, not just a calm range test. Capture apex height, offline dispersion, and roll consistency between seam orientations if not seamless.

Why quotes should lock mold + geometry drawing

Ask suppliers to quote with mold ID and geometry prints that show diameter, depth, edge angle, and layout. This makes samples traceable and procurement repeatable. It also prevents subtle geometry drift when chasing yield.

Seamless/high-symmetry layouts to reduce seam bias

If budget allows, pick seamless or high-symmetry patterns. These reduce directional bias. You’ll notice tighter side dispersion in crosswind A/B tests, and fewer complaints about “one box flying different” across lots.

Incoming QC: aero, size/weight, paint thickness

On arrival, verify diameter, weight, and concentricity. Measure paint thickness—too much paint can blunt edge angles and change depth, shifting flight. Run a wind A/B protocol on a pilot sample before releasing the PO balance.

OEM spec table — From spec to impact

| Spec item | Target / range | Test method | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mold ID + layout | Named 320–352 family | Drawing + visual audit | Repeatable flight |

| Dimple geometry | Depth/diameter/edge locked | Profile gauge / optical | Apex & drag control |

| Symmetry | Icosahedral / seamless | Pattern inspection | Lower seam bias |

| Size & weight | USGA-conform | Caliper / scale | Compliance & feel |

| Concentricity | Tight (supplier standard) | CT scan / cut & weigh | Dispersion |

| Paint thickness | Controlled window | Micrometer / destructive | Edge integrity & lift |

FAQ

Is 392 dimples better than 332?

No. Dimple count alone doesn’t guarantee longer or straighter flight. Geometry—depth, diameter, edge angle, and layout—determines apex and wind stability. Test the whole system, not just the number.

Think of count as a category hint, not a promise. A 392 pattern may trend flatter if paired with shallower cups, but a 332 with optimized edges can be just as stable and may carry better for certain speeds. Put both in a headwind/crosswind A/B, keep the same club, and let dispersion decide. If you cannot see consistent gains, the difference is marketing, not meaningful performance.

What’s the standard number of dimples on a golf ball?

There is no universal “standard,” but most modern balls fall between about ~300–400 dimples. Designers pick a count that supports their target window, then finalize with depth, edge, and layout.

You’ll see ~320–360 most often across 2- and 3-piece builds, ~330–388 in some tour-leaning 3-piece, and ~320–352 for many 4–5-piece balls. Outliers—<300 or >400—exist for specific goals. Judge them by your flight, not by novelty.

Do more dimples fly straighter in wind?

Sometimes—but only when paired with shallower depth and supportive edges. Edge angle and layout symmetry can outweigh the count. Always verify with wind testing.

Adding cups while making them shallower can trim drag and reduce ballooning. But if edge geometry is off, or symmetry is weak, crosswinds can still push shots offline. Look for high-symmetry or seamless patterns and a documented wind window. Then A/B in real wind to confirm.

Does USGA or R&A limit dimple count?

No. There’s no specific cap on the number of dimples. The rules cover size, weight, speed, and symmetrical flight. If a ball flies asymmetrically, it’s non-conforming regardless of count.

This freedom is why you see varied counts across brands. What matters is conformity and repeatable symmetry. For OEM buyers, request conformity documentation and, if possible, a symmetry test summary.

I hit too high—what dimple tendency should I look for?

Try families that lean toward more-and-shallow tendencies or are labeled mid/low flight. Your goal is to lower drag and apex while holding carry. Confirm in a headwind test.

Start with your current compression and cover. Then pick a model marketed for lower flight or wind, which often pairs higher count with shallower cups and tuned edges. If apex drops 10–20% without losing carry in headwind A/B, you’re on target.

I hit too low—can dimples help?

Yes. Fewer-and-deeper tendencies can raise lift and apex. Ensure your compression still matches your speed so you don’t lose ball speed while chasing height.

Look for mid/high flight labels. Keep your driver spin in a healthy range via compression and layers, then let deeper or lower-count patterns elevate the window. Re-check in cooler weather or higher elevations, where air density changes can shift apex.

Will softer balls go shorter?

Not inherently. “Soft” describes feel, not speed. Distance depends on compression match, launch, and spin. Many soft-feel balls are engineered to keep ball speed high for their target swing speeds.

If a soft ball’s compression is too low for your speed, it may over-spin or under-speed the driver. The reverse is also true: too high a compression can cost speed. Match compression first, then refine the flight with dimple tendencies.

For OEM, can I request “same count” to copy a leader?

No. You must match the full geometry and layout and, ideally, the mold ID. “Count-only” copycatting almost always fails to reproduce flight.

A credible RFQ locks mold ID, depth, diameter, edge angle, and layout. Ask for QC reports and run wind A/B before PO release. If a supplier resists sharing geometry basics, expect inconsistent flight even if the count matches.

Conclusion

Golf ball dimple count signals a tendency, not a guarantee. Treat it as one knob in a complete system: cover, compression, layers, consistency, then dimples to fine-tune the window. Choose by flight and wind, confirm with simple A/B tests, and—if you’re an OEM buyer—lock the mold and geometry, not just a number.

You might also like — How to Read Golf Ball Specs: Key Metrics & Real-World Impact